The outdated practice of giving dewormers liberally at set intervals without testing first has led to worms becoming resistant to many of the drugs that we use. This practice can’t continue. There’s now evidence of resistance to all classes of deworming drugs available in the UK and there is no prospect of new drugs being developed in the near future.

In the coming years, we could reach a point where many worms are resistant to all the dewormers available, which would be disastrous for equine welfare. It is essential that dewormer drugs are only used after testing and as part of structured programme of worm monitoring and control that is developed in partnership with your vet.

Resistance to dewormers

This state occurs when a proportion of the worms inside the horse are no longer killed by the dewormer.

Just as unnecessary antibiotic treatment promotes drug resistance, so the continued frequent use of deworming treatments is leading to dewormer resistance. Therefore, fixed interval deworming no longer has a place for worm control (with the possible exception of foals). If worm control is to be sustainable then dewormers should only be given in a targeted manner with their use being led by the results of regular testing.

Why does resistance develop?

Horses with access to pasture are naturally infected with a small number of worms that are no threat to health. This low level of infection may promote immunity, prevent allergies, and might protect the horse from developing a more substantial worm burden.

Every time we deworm a horse, the number of resistant worms increases. These then reproduce with one another and ultimately all the worms in the population become resistant so that the drugs no longer work1.

Eggs that are shed on the horse’s pasture will also develop into worms that no longer respond to treatment. Once this happens they will never regain their sensitivity to the treatment. The property will remain affected by resistant worms and any horses that move from the property will take resistant worms with them to infect other properties.

Impacts of resistance

- Resistance to one chemical increases the dependence on other chemicals resulting in a vicious circle where we become more and more dependent on fewer options.

- Fewer horses will be able to be kept on a certain pasture.

- Only five types of chemical drugs are available to treat horses in the UK for worms. There is evidence of resistance to all of these chemicals.

- If worms become resistant to all drugs, horses are at risk of serious disease from untreatable worm burdens, such as colic, weight loss and anaemia. Such burdens might be fatal.

What can we do to slow resistance?

Virtually every property has some degree of resistance in the herd’s worm populations. We can determine whether resistance is present to different dewormer drugs by using simple and easy Faecal Worm Egg Count Reduction Tests (FWECRTs). Knowing the pattern of dewormer resistance on the property allows future treatments to be planned with your vet to minimise the development of further resistance and risk of worm-related disease.

- Follow an evidence-based testing-led deworming programme, developed in partnership with your vet.

- Annual FWECRT, testing a different class of dewormer each year on rotation. Many vet labs offer this testing free of charge.

- Good pasture management which is more effective than any dewormer treatment.

Minimising the worm burden

Sensible management practices can massively reduce exposure of horses to infective worm larvae (the stage of the worm living on the pasture that has the potential to infect horses). It also interrupts the lifecycle of the worms. Removing faeces (and therefore worm eggs) from pasture has been shown to be far more effective than using chemical dewormers.

Some good practices to follow include:

- Pick up droppings at least twice a week, more frequently if possible.

- Rotate paddocks for rest periods. Ideally keep a pasture free from horses for several months to give time for worm eggs and larvae to die. In hot, dry weather eggs and larvae will die faster than in mild damp weather.

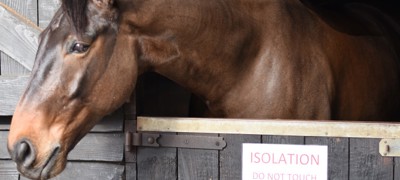

- Quarantine new horses coming to the yard, test and treat them for worms as advised by your vet. Performing a FWECRT is a really good idea to know if incoming horses carry resistant worm burdens so they can be treated effectively with other types of dewormer before mixing with the rest of the herd.

- Put foals onto ‘rested’ pasture (land that hasn’t had any other horses on it for a period of time, ideally 12 months).

- Don’t over-stock your paddocks.

- In well-managed foals, FWEC testing can be performed from the outset. Seek vet advice for your specific circumstance. Consideration needs to be given to Parascaris and Strongyloides as well as redworms (Cyathostomins).

- Cross graze your pasture with other grazing species to break worm life-cycles. Sheep/goats/cattle will clean the pasture of larvae and eggs without becoming ill themselves (and vice versa). Don’t forget to speak to your vet about a protocol for monitoring worms in the other species on your pasture.

- Plan your pasture management and keep records.

Deworming your horse

Deworming should only be performed where strictly necessary to prevent the risk of disease or to limit pasture contamination with worm eggs.

If vet advice or testing suggests that deworming is necessary, the video below will take you through the correct steps to worm your horse safely and accurately.

play-circle

play-circle

Watch

How to Safely and Accurately Deworm your Horse

Mare & Foal deworming programme

Foals require special consideration as they have lower immunity than adult horses and are at risk from a greater range of worms. On well managed properties, a testing-led plan for foals can be implemented with appropriate vet advice. The traditional practice of routine treatment of mares prior to foaling should not be necessary if mares are well managed and tested appropriately. Foals should be kept on pasture that has been rested from horses for as long as possible, and the use of the same paddocks for youngstock year-on-year is not recommended2. When developing programmes for foals you should work closely with your vet.

Dangers of exposing the environment to dewormer drugs

Deworming drugs are not selective for horse worms and will kill a range of invertebrates if they come into contact with them. Some of the most common chemicals used to deworm horses are highly toxic to invertebrates such as dung beetles and to aquatic life, meaning they pose a real threat to our rural ecosystems and soil quality. The chemicals remain active in manure for many months after they pass through the horse and can therefore have a lasting effect on the environment.

To prevent contamination, bring the horse onto a surfaced area to administer the dewormer, that can be easily cleaned if necessary - rather than treat them in the field.

Poo pick regularly post deworming, so any contaminated droppings are not left on the field, and store manure for as long as possible (months into years) if spreading it back onto fields.

References

chevron-down

chevron-up

1) Nielsen, M.K. (2021) Parasite faecal egg counts in equine veterinary practice. Equine Veterinary Education.

2) Rendle, D et al. (2019). Equine de-worming: a consensus on current best practice. UK Vet Equine.